Functional Tuple Language (FTL)

Introduction

FTL is a very simple programming language in algebraic form that is primarily composed of functional tuples in the form of (t0, t1, …) and tuple mapping operator -> .

The tuple is usually used as data structure in many programming languages. We make it functional by extending each element into a function, hence functional tuple. We also introduce a mapping topology between elements of two consecutive functional tuples with a operator ->. Rules and special tuple element selectors are defined for the mapping topology. We call this tupology (tu-ple + to-pology).

In FTL, the only intrinsic operator defined at language level is the mapping operator ->. However, a set of symbol characters are provided to define any operators with one or more such characters. Examples are arithmetic operators +, -, *, and /

There are no intrinsic control statements such as for or while loops, as well. This is because such control statements in the other languages can be expressed as functions are they actually defined as external functions.

All these make FTL very simple with just the following elements:

- Functional tuple in form of (t0, t1, …) with

0based index; - Mapping operator

->between tuples; - Stateless pure function or operator definition statements with keyword

fn; - Import statements with keyword

importallowing grouping and importing functions across modules; - Application statements for performing computations composed of all above.

For example, if ... else is defined as ternary operator ? : in ftl/lang module, as well as for ... loop as ?< and while loop as <? in the same module.

Modules

Functions and operators can be grouped into a module and imported into other modules. A module is represented as a file with extension “.ftl”.

Any function or operator in a module can be imported, except the ones with name prefixed with _, which is regarded as private to the module.

When a module is imported by another module, the already imported elements by that module are not automatically/implicitly get imported. In other words, any elements of a module have to be explicitly imported anywhere it is needed.

Indentations

With functional tuples and mapping operator, a complex algorithm may be expressed in a long statement spanning across many lines, which may be hard to read. Because of this, we adopt a very special form of indentation. All statements start from a new line without any leading space, and a statement may span many lines with each continuation line with at least one leading space or tab. You have freedom of choosing any number of space or tab characters for indentation.

Language Elements

Key Words

import ... [as]- for importing other modules;fn- for defining a function;true,false- constant value for logical true and false;_and_\d+$such as_0,_1, etc. They are reserved as tuple selectors.

Importing Functions/Operators

Using import or import ... as to import functions from the other modules.

Libraries

A module can be defined as a library in lib directory.

When importing all functions/operators from a library, such as lib/lang.ftl, import as:

import ftl/lang

Application Modules

Often an application may be split into many modules in the same directory or in hierarchical directories.

When importing from such application modules, use relative directory, such as:

import ./submodule1

If you just want to import a number of functions/operators, use square brackets enclosing them with comma delimited, such as:

import ftl/lang[+, -, /, >]

For prefix/postfix/n-ary operators, they have to be quoted as:

import ftl/lang['- ', '? :']

where '- ' with a space appended referring to prefix - so to distinguish from binary -.

For postfix operator, a space has to be prepended, such as factorial postfix operator !, which has to be imported as:

import ftl/lang[' !']

Basic Data Types

- number

- string

- boolean -

true,false - list with elements separated by comma and wrapped in paired square brackets

- tuple with above as elements

Functional Tuple

A functional tuple is composed of a pair of parentheses enclosing elements separated by comma as follows:

(a:t0, b:t1, …, c:tn-1)

where a, b, and c are optional names to each element. Element names can be any identifier characters except tuple selectors.

There is no dependency among the elements in one such tuple, thus each element can be computed independently and concurrently.

The element ti can be of the following:

- constants with basic data types

- functional tuple

- named function or inline anonymous function (lambda expression)

- function with partial arguments

- unary (pre or post), binary, or n-ary operator expressions

Tupology (Tu-ple to-pology)

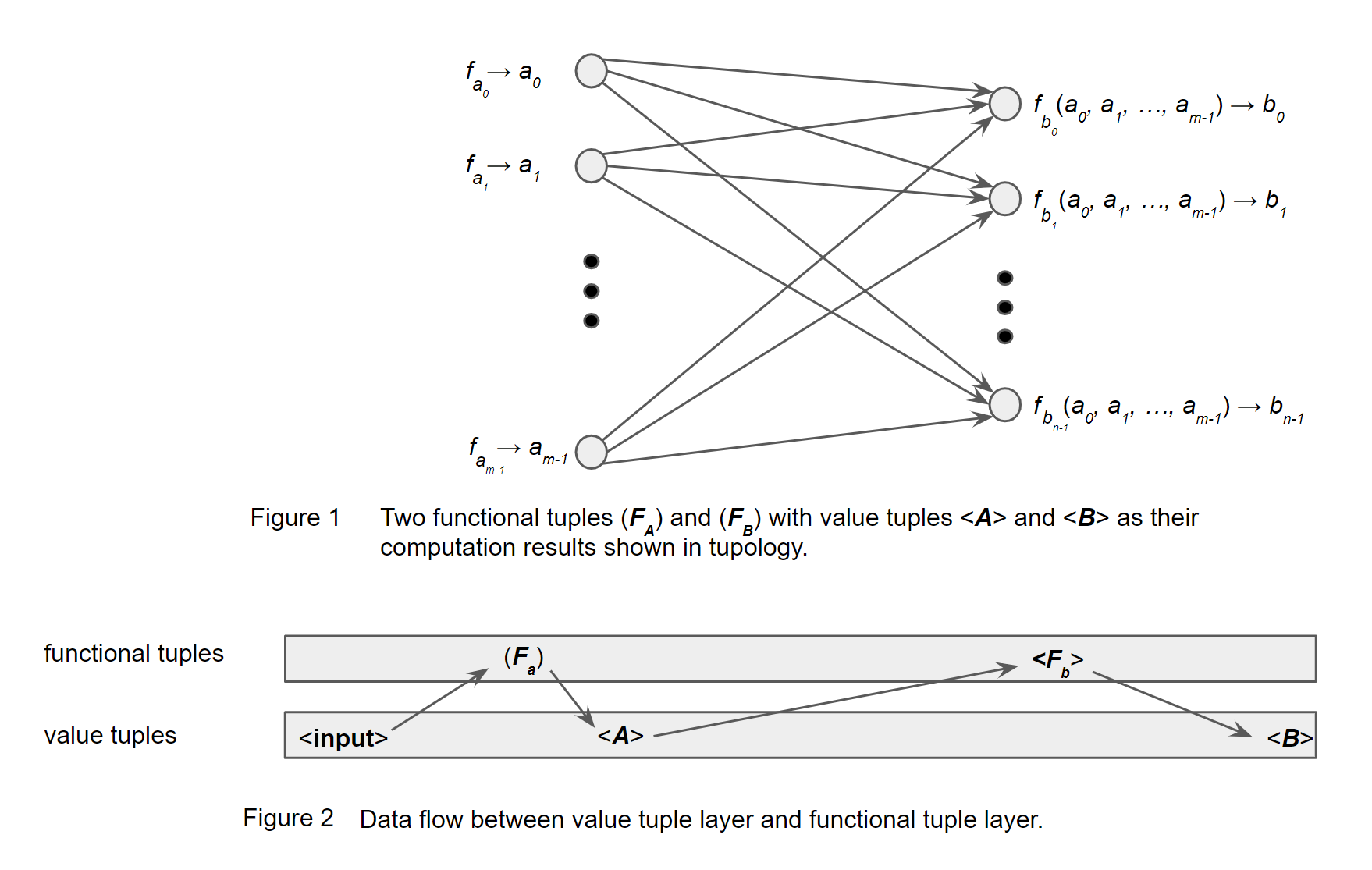

Assume there are functional tuple (Fa)=(fa0, fa1, …, fam-1) and (Fb)=(fb0, fb1, …, fbn-1) connected with mapping operator ->, where parentheses around Fa and Fb is just indicator that they are functional tuple.

When an input is sent to Fa, a value tuple is generated as:

<A>=Fa(input).

where angle brackets around A is an indicator that A is a value tuple.

This <A> is then sent to Fb to produce value tuple as:

<B>=Fb(A).

This process is named as tupology which is shown in Figure 1 below, where (Fa) has m elements each as function fai and (Fb) has n elements each as function fbj.

The computation result for each element is essentially its function applied to results of all element from the previous functional tuple. For example, tuple (Fb) shows more completed form in Figure 1.

Figure 2 above shows the same mapping in different form where functional tuples and value tuples are separated into two vertical layer and data computation process is the data flowing between the two layers.

For an application with the chain of tuples, the computation is the process from the first input and functional tuple and the result value tuple is sent to the next functional tuple, and the same process repeats until the last functional tuple.

With tuple and mapping operator, an expression of arbitrary length can be created. In other words, a complex computation can be written into one such algebraic expression.

The src/ftl/example/fft.ftl is an example, where fast Fourier transform (FFT) is expressed in just one expression.

Tuple Element Selector

Tuple element selector is the most important mapping. It allows selection of tuple elements from value tuple from preceeding functional tuple.

- Whole tuple selector,

_, is to select the whole input to it. Thus, it serves asidentity functioninFTL. - A number following

_is tuple element selector, e.g.,_0selects the first element and_1selects the second one, etc.

The tuple selectors are reserved and cannot be used as identifiers.

Examples:

(pi:3.14159, e:2.71828) -> _0 == 3.14159

(pi:3.14159, e:2.71828) -> _1 == 2.71828

(pi:3.14159, e:2.71828) -> e == 2.71828

Identifier Selector

An identifier can be used to select the named tuple element.

Examples:

(pi:3.14159, e:2.71828) -> e == 2.71828

Functional Tuple as Data Structure

A functional tuple can be seen as a data structure as well. This is because in the end of computation, the result of a functional tuple is a value tuple with element accessible either sequentially as a list with sequential tuple selector, such as _0, _1, etc., or as a map with identifier selector.

Implicit Whole Tuple Selector

Besides the tuple selectors defined above, the whole value tuple will be applied to the expression of each tuple element when it is not an element selector. In other words, expression of any non-tuple element selector is a whole tuple selector.

For example:

(pi:3.14159, e:2.71828) -> sin

is equivalent to sin(pi:3.14159, e:2.71828).

The computation of an expression in FTL is the process of applying the above rules to each tuple element when the value tuple from preceding functional tuple is applied.

Lastly but most importantly: a functional tuple can only see its immediate value tuple, not any other tuples beyond. Because of this, each tuple in an expression is ultimately a lambda expression.

Functions

Any explicit function declaration has the following form:

fn name([argument list])

where fn is the reserved word, and arguments are names delimited by comma.

A function has to be declared before it can be referenced/used. Thus, there is no way to define functions circularly referenced.

A function can be recursive though (such as in fft.ftl) in its own definition.

Lazy Argument Computation

A parameter can be in form of function. When this is the case, the actual passing argument will be wrapped as a function for delayed invocation inside the function implementation.

For example, the ternary operator ? : is written in such a way that at time of computation, either is_true() or otherwise() is computed based on the result of if_true but they will never be computed together. This will reduce unnecessary computation.

Parameter as Tail Function for Reducing Call Stack Depth

A parameter can be defined as a tail function (function signature with name ends with $) as well. At runtime the corresponding expression will be wrapped as a tail function and returned to calling stack without being invoked. Such mechanism is specially designed to reduce depth of call stacks when dealing with recursive functions. In the end, no matter how many recursions, the call stack depth can be maintained as a constant.

You have to make sure that when writing a function with tail parameter, it is really a tail.

Example is in operator ?? ::, where either is_true$() or otherwise$() will not be computed within the operator. Instead, one of them will be returned to the calling stack, reducing one level of call stack depth.

Other examples are operator || and &&, where computation of y$() can be deferred into the calling stack.

Parameter Default Value

A parameter can have default value which will be used when not provided at time of invocation.

Extra Arguments

With parameters defined, a function may be invoked with extra arguments which will not be passed to the function.

For example:

(3.14, 2.718) -> sin

will be sin(3.14) at runtime with 2.718 not passing to sin.

This makes it very easy for tuple composition as well as extending existing tuples without functionality change.

Partial Function

When calling a function by providing less than needed arguments, it returns a partial function automatically.

Currying

Because of this partial function feature, you are able to invoke a function in a currying way by invoke it n times with each time providing just one argument, where n is the number of parameters.

@sideffect

A sideffect (short for side effect) is such a special function mostly implemented with javascript to cause side effects to the outside of the computation, such as writing to a file, printing to console, or painting on canvas.

When such a function is used as sideffect, it should be prefixed with @.

A sideffect should not change the input for computation. In other words, an expression with @sideffect should produce the same computation result as if without @sideffect.

To achieve this, a copy of the input is passed to a sideffect and its returned value is discarded to prevent possible side effect for computation.

At run time, it is built as part of the mapping preceding the expression and it can be completely ignored when reasoning.

Function Composition

Function composition is intrinsic to operator ->:

f -> g

You can also do:

g(f)

For example:

3.14159 -> sin(cos)

3.14159 -> cos -> sin

are equivalent.

Operators

Not like other languages with many pre-defined operators in language such as arithmetic operators, this language does not have any intrinsic operators except ->. However, it gives freedom of defining arbitrary operators out of a character set. For example, all arithmetic operators in lib/lang.ftl are defined as external operators, not intrinsic ones. The syntax allows definition of not only binary, but also prefix or postfix or n-ary operators.

Operator Symbols

Operator can be defined with one or more characters from the following:

! % & * + \ - . / : < = > ? ^ | × ÷ ∏ ∑ ∕ ∗ ∙ √ ∛ ∜ ∧ ∨ ∩ ∪ ∼ ≤ ≥ ⊂ ⊃ ¬ ∀

Prefix operator

A prefix operator is declared with operator followed by the operand name.

For example, unary minus operator:

fn -val

Postfix operator

A postfix operator is declared with operand name followed by the operator.

For example, increment operator:

fn val++ -> val + 1

Remember in FTL, all functions are pure and stateless, val++ does not mean the val itself has value changed, but just its value incremented and pass to next functional tuple.

Binary Operator

A binary operator is defined as a normal binary operator form with the operator in between of the two operands:

fn op1 op op2 -> ftl_implementation

fn op1 op op2 {

// javascript implementation

}

For example, max operator is defined in FTL as:

fn x ∨ y -> max(x, y)

and addition operator is defined in javascript as:

fn x + y { return x + y }

N-ary operator

An n-ary operator is declared with operand name followed by the first operator and repeat with the same pattern for all rest operands and operators and end with the last operand:

fn operand1 op1 operand2 op2 operand3 -> ftl_implementation

fn operand1 op1 operand2 op2 operand3 {

// javascript implementation

}

For example, consecutive comparison:

fn x < y < z -> x < y && (y < z)

Operator Precedence and Associativity

When multiple operators are involved in an expression, parentheses ( and ) can be used to specify precedence. Otherwise, each type of operator follows the rules in the corresponding subsections below.

Overall, user defined unary operator has highest level precedence than binary/n-ary operators.

Unary Operators

When multiple prefix or postfix operators are applied to the same expression, most inner one has highest precedence and most outer one has lowest precedence.

When both prefix and postfix operators are present, prefix operator has higher precedence.

In other words,

pre-op1 pre-op2 pre-op3 expr post-op1 post-op2 post-op3 expr

is equivalent to

(((pre-op1 (pre-op2 (pre-op3 expr))) post-op1) post-op2) post-op3.

Binary Operators

User defined binary operators have left associativity, which reflects the computation sequence and precedence as well.

Thus,

expr1 op1 expr2 op2 expr3

means

(expr1 op1 expr2) op2 expr3

In other words, when an expression involves in multiple binary operators, the most left operator has highest precedence and most right one has lowest precedence.

Example:

5 - 2 * 3

Since this expression involves in two operators - and * and operators are left associative, it is equivalent to:

(5 - 2) * 3

If 2 * 3 needs to be computed first, do it as:

5 - (2 * 3)

N-ary Operators

FTL allows definiton of n-ary infix operators. For example, the ternary operator ? : is defined in ftl/lang.ftl library.

N-ary operators cannot be nested in the middle without parentheses. Using ? : as an example. We can have 1 < 2 ? (2 < 3 ? true : false) : false but 1 < 2 ? 2 < 3 ? true : false : false will give error as ERROR: N-ary operator '< ? < ? : :' not found!

This is because the process of resolving operator is to search from the longest possible n-ary operator < ? < ? : :, then starts by removing one from right and search again for < ? < ? :, and repeat the same process until it goes down to <.

If < is found, it will repeat the same process for ? < ? : :, etc., where ? < will not resolve to any known operator combinations.

This process is actually used to resolve unary/binary operators as well.

For example, the process of resolving 5 - 2 * 3 is as follows:

- Does n-ary operator

- *exist? - If not, does binary operator

-exist? - If yes, then does binary operator

*exist?

If one defines a ternary operator - * as follows:

fn a - b * c -> a - (b * c)

Then 5 - 2 * 3 will be resolved using this operator and stop at step 1 above.

With the above n-ary operator - * defined, one can write the following using this operator in a concatenate way (not nesting in the middle):

5 - 2 * 3 - 4 * 5

which will actually be resolved as:

(5 - 2 * 3) - 4 * 5

and the result will be -21.

Intrinsic Operator ->

Please note that all user defined operators are in form of functions with strict evaluation except the ones with parameters in form of functions or tail functions. The intrinsic mapping operator ->, however, has the form of binary operator but in essence does not do strict evaluation.

This is because it evaluates the left-hand side first then pass the result to the right-hand side before doing evaluation there. In other words, the right hand side evaluation depends on result of left-hand side evaluation.

To achieve this, the intrinsic operator-> always has lowest precedence when user defined operators appear at the same level.

For example,

(a:3.14159, b:2) -> a * b + b -> _0 + 2

is equivalent to:

(a:3.14159, b:2) -> (a * b + b) -> (_0 + 2)

The operator -> is also associative:

a -> b -> c == ((a -> b) -> c) == (a -> (b -> c))

Extending Operator ->

Operator -> can be extended in the following regex form:

[op_symbol]+->

When being used, such binary operator does not need the ending ->, though the full operator needs to be imported. The FTL runner will figured it out in the calling expression.

There are two such operators defined in ftl/lang:

fn a .-> bfn a ?.-> b

.-> is defined as element accessor, such as:

a.b

where a is a tuple. If b exists in a, it will be returned. Otherwise null will be returned.

a ?.-> b is condition element accessor. It can be used as a?.b which returns either b or an empty tuple, thus condition element accessor can be chained as:

a?.b?.c

without throwing exception if b is not in a.

Another such operator is defined in ftl/list as:

fn list .->-> f

which is a lift operator that lift function f for a list.

For example:

[3.14, 6.28] .-> sin

Please note that such new operator extending -> will have precedence the same as regular binary operator, not the one that -> has.

Binary Operator Prefix

Besides defining different kinds of operators, one can define a binary operator prefix (not prefix operator) that can be applied to any binary operator.

A binary operator prefix can be declared as:

fn a [prefix]<op> b

where [prefix] is the actual prefix with any number of operator characters, and followed by < and > with the op as a generic parameter for any binary operator.

A typical such prefix is the one . defined in ftl/list to lift all arithmetic operator to be applicable to arrays as:

fn a .<op> b

With this prefix . defined, the following expression will work with arithmetic operators that are defined for scalar values:

[1, 2, 3] .+ 1 == [2, 3, 4]

[1, 2, 3] .+ [4, 5, 6] == [5, 7, 9]

The prefix should be defined in such a way that it still works with the original types.

For example:

1 .+ 2 == 3

Lambda Expression

Lambda expression is an anonymous function which is supported in tupology expressions.

A lambda in an expression is in form of a function with a very special name $.

For example:

(1, 2, 3) -> ($(x, y, z) -> x * y * z)

where ($(x, y, z) -> x * y * z) is a lambda expression.

Array operations

Array is defined and backed by javascript array.

Array initializer

Array elements can be initialized as: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], or with interval such as [1:2:5] which results in [1, 3, 5], etc.

Array selector

Array elements can be selected in the following way:

- Select singe element:

[m]means selecting mth element. - Select a sub-array with range specified:

[m:n]means selecting from mth element inclusive to nth element inclusive. - Select a sub-array with

beginspecified:[3:]means selecting a subarray starting from 3rd element to the end of the array. - Select a sub-array with

intervalspecified as well:[3:2:]means selecting a subarray starting from 3rd element with interval of 2 to the end of the array.

Example:

[1,2,3,4,5] -> _0[1:2:]

returns [2, 4].

Raising function for each array element

Any function/operator defined for non-array can be raised for array with .-> prefixing the function.

For example:

[1, 2] .-> cos

is equivalent to:

[cos(1), cos(2)]

Arithmetic operators can be raised by prefixing with binary operator prefix “.”.

For example:

[1, 2] .* 2 will result in [2, 4].

For loop as a function

The for and while ... do loops can be easily expressed as functions. Same is do ... while loop.

For details, see implementation in lib/lang.ftl, and usage in biomial-coeff.ftl, map.ftl, reduce.ftl, and square-root.ftl, etc.

Function/operator implementation with Javascript

Any function/operator can be implemented with javascript wrapped with curly brackets. Remember all javascript lines needs to start with at least one space except the end curly bracket.

For example:

fn -val { return -val }

Or

fn -val {

return -val

}

Function/operator implementation with ftl

When implementing with ftl, it starts with operator ->.

For example:

fn x! -> x == 0 ?? 1 :: (x * (x - 1)!)

Application

Statements for application are all in form of FTL in tuples (...) and mapping operators ->.

Examples and Demos

Examples and demos can be found here.